NASA’s Mars rover Perseverance, the most advanced robotic astrobiology lab ever flown to another world, neared the end of its seven-month, 293-million-mile (470-million-km) journey on Wednesday, hours away from a daredevil landing attempt on the Red Planet.

With 370,000 miles (596,000 km) left to travel, Perseverance was hurtling through space on track for a bull’s-eye touchdown on Thursday inside a vast basin called Jezero Crater, site of a long-vanished Martian lake bed and river delta, mission managers said on Tuesday.

The primary objective of the two-year, $2.7 billion mission is a search for evidence that microbial organisms may have flourished on Mars some 3 billion years ago, when the planet was warmer, wetter and presumably more hospitable to life.

Larger and more sophisticated than any of the four mobile science vehicles NASA landed on Mars before it, Perseverance is designed to extract rock samples for future analysis back on Earth — the first such specimens ever collected by humankind from another planet.

“I can tell you that Perseverance is operating perfectly right now, that all systems are go for landing,” Jennifer Trosper, deputy project manager at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory near Los Angeles, told an online briefing.

Mission engineers sent the spacecraft a command on Monday night activating onboard systems for atmospheric entry, descent and landing, Trosper said.

Data received from the rover, still packed inside the capsule of the Mars-bound “cruise” stage of the spacecraft, shows the vehicle “headed exactly where we want to be,” with no last-minute course corrections anticipated, she said.

Nevertheless, NASA engineers acknowledge that getting the six-wheeled, SUV-sized rover safely to the Martian surface is the riskiest part of the mission.

Much depends on the result. Building on nearly 20 U.S. outings to Mars dating back to Mariner 4’s 1965 flyby, the success of Perseverance would set the stage for conclusively showing whether life has ever existed beyond Earth, while paving the way for eventually sending humans to explore the fourth planet from the sun.

Perseverance is carrying some novel demonstration projects as well. They include a miniature helicopter built to test the first powered, controlled flight of an aircraft on another planet, and a device to convert carbon dioxide in Mars’ atmosphere into pure oxygen.

The rover also comes with a weather station, 19 cameras and even two microphones that NASA hopes will give greater sensory depth to the images it records.

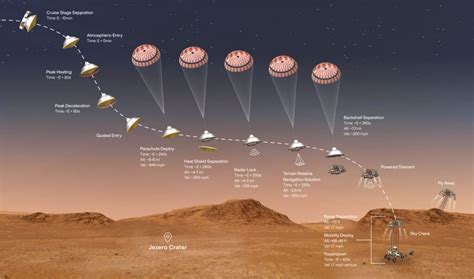

Safe arrival hinges on a self-guided, seemingly far-fetched sequence of events unfolding with flawless precision within seven minutes — the time it should take the rover to get from the top of the Martian atmosphere to the floor of Jezero Crater.

An 11-minute lag in one-way radio transmission from Mars makes Earthbound control of the rover’s descent impossible.

The spacecraft is expected to pierce Mars’ atmosphere at 12,000 miles per hour (19,300 kph) and angled to produce slight aerodynamic lift while jet thrusters adjust its trajectory.

A jarring, supersonic parachute inflation to further slow the descent will give way to deployment of a jet-powered “sky crane” vehicle that will fly to a safe landing spot, hover above the surface while lowering the rover on tethers, then fly away.

If all goes well, the interval that NASA half-jokingly calls the “seven minutes of terror” will end with the rover intact amid a Martian landscape long coveted by scientists for its rich potential as a geobiological laboratory.

What makes the crater’s terrain — deeply carved by long-vanished flows of liquid water — so tantalizing as a research site also makes it especially treacherous as a landing zone, requiring next-generation autopilot technology never before used in spaceflight.

Still, as Thomas Zurbuchen, NASA’s associate administrator for science, conceded, the outcome is far from assured.

“Mars is hard, and we never take success for granted,” he said.